I’m holding an 8th grade schoolbook. These middle schoolers will have the chance to learn about naval battles, from Demetrius at Salamis in 306 BC to Nelson at Trafalgar in 1805, as well as read about the lives of Rembrandt and DaVinci, while being introduced to stories ranging from Jesus’ Last Supper to Paris’s patroness saint and her brave stand against Attila the Hun - all set to a soundtrack featuring the likes of Elgar, Verdi, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Wagner, Haydn, Handel, and Rachmaninoff. Of course, none of this will strike the children as particularly odd by this point - they’ve been diligently learning stories of Jesus, John the Baptist, the kings and queens of Spain and England, the daily life of children in Holland in the 19th century, and the lives of artists like Raphael, Van Dyck, Murillo, and Millet, to a soundtrack of Schumann and Brahms, since they were in first grade.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: must be one of them fancy new private schools. One of the trendy classical Christian ones of the kind that have been popping up all over the place lately. Probably already has a waiting list a year long and tuition priced at an arm and a leg - heck, they can charge anything they want, they’ll still have a wait list, as parents flee the public school system in droves, right?

What if I told you… this is a public school textbook. Yes, really! No, I haven’t been drinking. And no, it’s not some charter school in a deep red state that got infiltrated by radical “Christian nationalists” and managed to sneak in some soul-expanding content before the local chapter of the ACLU noticed. This is a run-of-the-mill, regular, unexceptional public school in Illinois.

What’s the catch? Well, the book dates from… 1927.

Please allow me to introduce you to Katherine Morris Lester, Director of Art Education in the public schools of Peoria, Illinois about a century ago. With the contribution of her colleague Eva G. Kidder, Director of Music, Peoria Public Schools, Lester crafted a series of short little books, Great Pictures and their Stories: Interpreting Masterpieces to Children.

I think you will get a kick out of looking through them, I know I did. So here goes:

There are nine books in all, each as thin as can be.

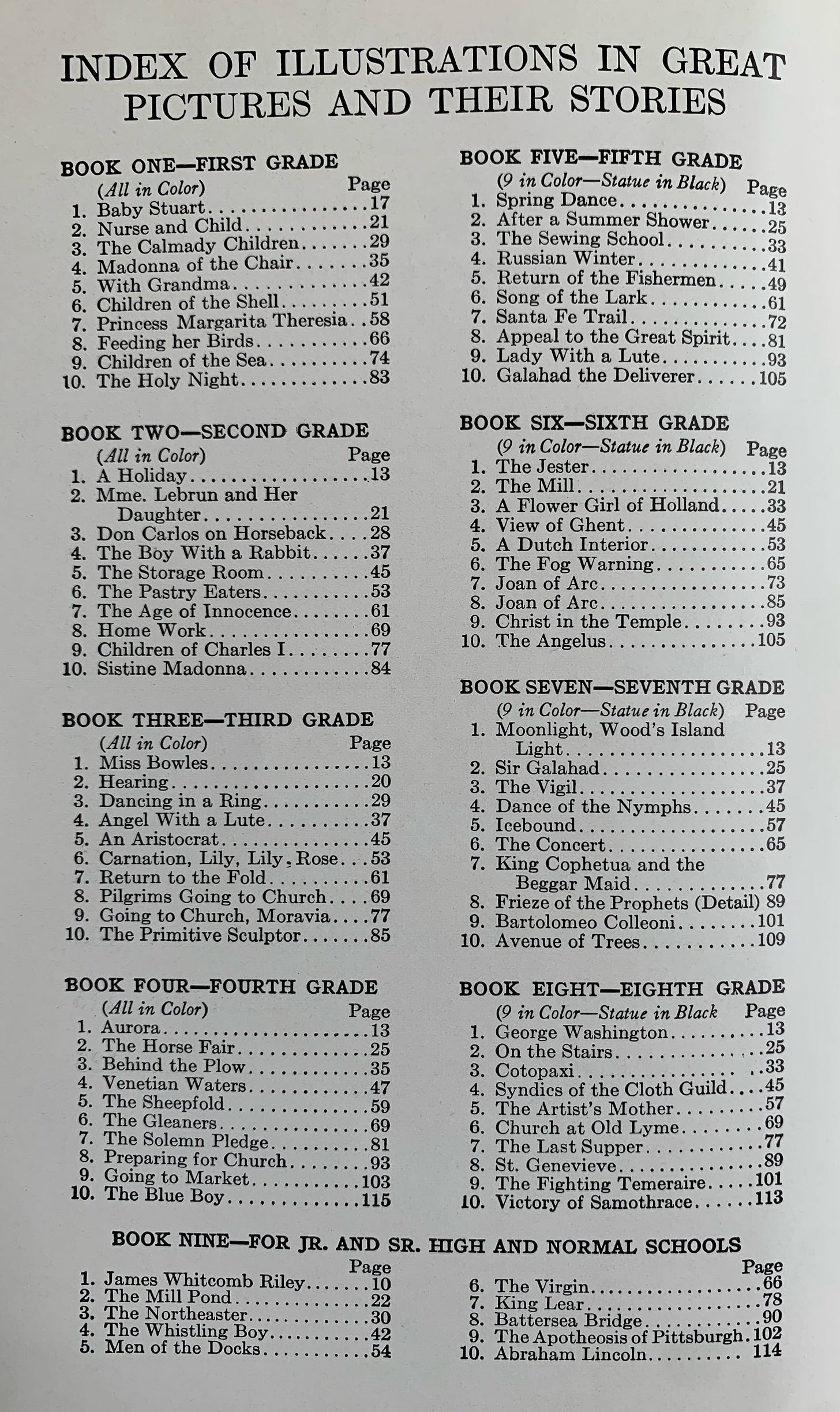

Book one is aimed at first graders, written with very simply vocabulary, and each year brings some advancement in both vocabulary and depth of analysis, culminating in book nine, for ninth grade and up. Each book contains 10 works of art, mostly paintings, some statues. Here’s the complete list:

My wife stumbled across books three and five in a huge pile of old books at a local antique store a few weeks ago, got them for five bucks combined. Breton’s The Song of the Lark is one of our favorite paintings, so we were enthralled and tracked down every other book of the series on eBay. For each work, Lester gives an age appropriate description of the scene, its artistic technique, and the life of its creator.

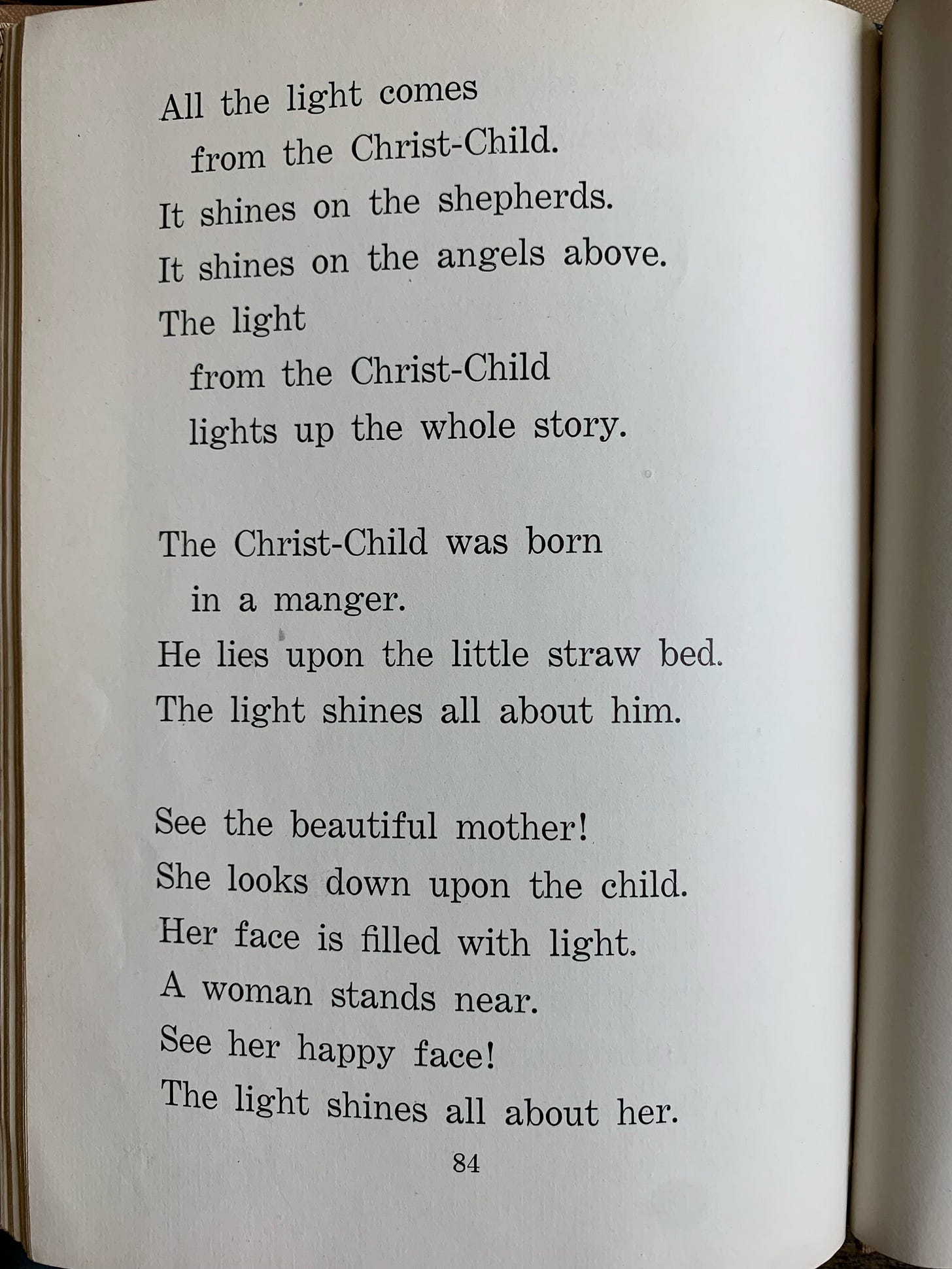

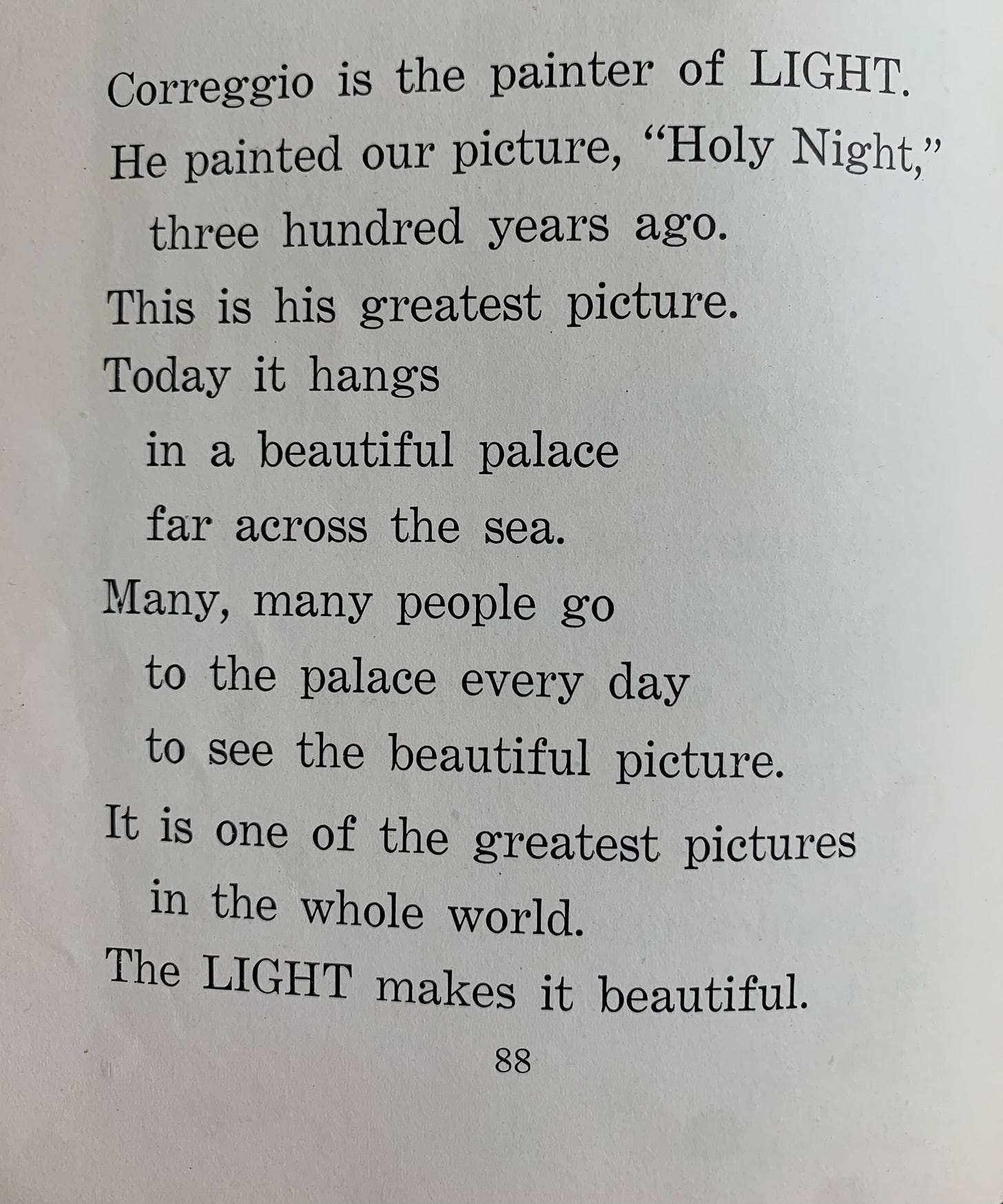

Here’s an example from first grade:

Each section concludes with some discussion questions and, thanks to Kidder’s input, appropriate musical selections. Staying with book one:

Hopefully if you’re reading this you can handle more than a first grade reading level, so let’s check in with the middle schoolers. From book eight, telling the story behind de Chavannes’ murals of St. Genevieve watching over Paris (which, the students learn, are “in the magnificent building of the Pantheon” and “are the pride of the French nation”):

I can’t believe I am about to write this about a public school textbook, but not every page is explicitly about Christianity, I promise. For the last excerpts, also from book eight, I hope you will enjoy this historically charged masterpiece by Turner, and Lester’s wonderful recounting of the artist’s life:

Can anyone read pages like that without a big smile on their face? The musical accompaniments for Turner, by the way, are selections from Mendelssohn and Chopin.

Don’t sleep on the music. Lester certainly didn’t. From her guide to fellow teachers at the end of each book:

I will try my very best to be brief, as I think Lester’s book does all the talking for me. Some classical education advocates were having a lot of fun last week at the expense of a corporate media organization, who, in a hit piece against Governor DeSantis’ attempts to reform education in his state, made the rather extraordinary claim that “classical education is largely pioneered by Hillsdale College.” I suppose that is quite the feather in the cap for the fine folks at Hillsdale, but, as they would be the first to object, education focused on great works of the past and on the true, the good, and the beautiful has been around for a long, long time. Indeed, as leading classical education advocate Jeremy Wayne Tate (no, not that Tate) put it,

The truth is that 100% of universities passed down classical education until about 50 years ago when many universities went insane. Hillsdale didn’t create something new. They simply stayed sane.

Now, I don’t even think Lester herself would necessarily call what she was doing a classical education. She considered her project of picture study a “progressive” one, embraced by “nearly every progressive city.” Yes, folks, back in the day, the leading progressive educators in the most progressive cities were united in their attempts to get little kids to look closely at baby Jesus, not drag queens. And nobody - nobody! - thought this would in any way violate the Constitution. Indeed, it’s almost like everybody understood the country’s public schools were specifically founded in order to spread “religion, morality, and knowledge.” Odd, that!

Funny, too, the absence in the excerpts above of any soulless, worksheet-based, repetitive, Gradgrindian dullness, isn’t it? I just see beautiful pictures, beautiful music, beautiful stories. With no Common Core skills to drill, what on earth will they put on the standardized tests? Remember when I told you that kindergarten was invented with the explicit purpose of getting kids to sing and dance and play and garden, without a hint of worksheets or state standards? Elizabeth Peabody invented American kindergarten to cultivate wonder in children. Katherine Morris Lester, too, had a mission statement for her work, reproduced in every volume of her series:

To clarify, for the education school professors and other contemporary curricular experts who might be reading this, by “enrich,” Lester does not mean help kids get a higher salary in a competitive job market. She is referring to something far deeper and far more valuable. Something, as I hope you can all now appreciate, that our schools - yes, even our public schools - used to care about a great deal indeed.

I could go on and on, and I’m sure I’ll revisit this theme, but like I said, for now I think it’s more than enough to let Lester do the talking.

We are not the invaders, we are not the revolutionaries, we are not the extremists. We are simply the ones who stayed sane as the world went mad…

Thank you for reading, bless you and yours, and have a wonderful, beauty-enriched weekend! Oh, and maybe check out your nearest antique dealer…

Loved this post Adrian! We have a complete set of McGuffey readers which remind me very much of the readers you shared here. I grew up in Switzerland, where kindergarten indeed still remains a place to sing, dance, and play; reading, writing, and math start in primary school. We were merely taught to write our name, and the rest was richly filled with creative games, stories, plays, craft - not a single worksheet :)

I taught my 3 daughters to read using McGuffey readers. With similar topics and excellent results. And Dr. Gaty, please do not be ashamed of promoting pedagogical material coming from Christianity--please (O Canadian) be aware that our whole USA public school system got its start in Boston, 1647 (actually a bit earlier but with less success), with the "Old Deluder Act"--requiring every town of 50 families to render every little boy AND girl literate, so that they could read the Bible and not be misled by 'the Old Deluder' (it was only about 100 years earlier that you got executed for printing in/translating [Tyndale] the Bible into English). Every town of 100 families had to provide an academy (grammar school) to get boys ready for Harvard--then a Congregational seminary.