Have you heard of Robert Clive? Here, from Winston Churchill’s A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, is a précis of his youth:

He was the son of a small squire, and his boyhood had been variegated and unpromising. Clive had attended no fewer than four schools, and been unsuccessful at all. In his Shropshire market town he had organised and led a gang of adolescent ruffians who extorted pennies and apples from tradesmen in return for not breaking their windows. At the age of eighteen he was sent abroad as a junior clerk in the East India Company at a salary of five pounds a year and forty pounds expenses. He was a difficult and unpromising subordinate. He detested the routine and the atmosphere of the counting-house. Twice, it is said, he attempted suicide, and twice the pistol misfired.

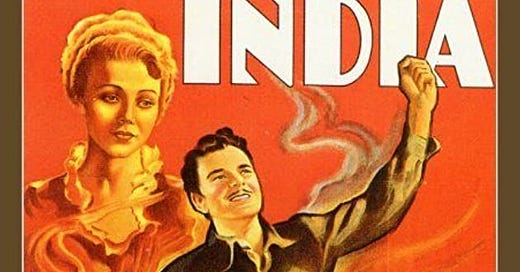

Why would Churchill devote almost a whole chapter of his epic history to this terrible student, this troubled juvenile delinquent who hated his dull clerical career? Well, because this hopeless student, this depressed clerk, was soon to become the world-famous “Clive of India.” The rest of the story: “not until [Clive] had obtained a military commission and served some years in the armed forces of the Company did he reveal a military genius unequalled in the British history of India.” For better or worse, this no-account schoolboy “would found the rule of the British in India.”

My goal is not to debate the merits of empire – though you of course are more than welcome to do so in the comments. My sole purpose is to highlight two lines from above:

“Clive had attended no fewer than four schools, and been unsuccessful at all.”

“a military genius unequalled in the British history of India.”

At first glance, this may seem a surprising juxtaposition. It shouldn’t be. If success in school were about daring, grit, leadership, and visionary strategic thinking, then Clive may very well have made the honor roll. Success in school, however, is far too often about rewarding those who sit quietly and dutifully at their desks, repeating what they are told. There is nothing wrong with that! I personally was great at it. But nobody’s gonna be putting my statue up anytime soon. Clive’s studious contemporaries, his classmates who excelled at all four of those schools, may have ended up as East India Company clerks, too – only they were probably a lot better at clerking, and a lot happier with the work, than he was. The more battles the failed student won, the more territory there was for the teacher’s pets to skillfully administer. I’m not making an argument for the superiority of one path over the other, only saying that we oughtn’t forget to leave room for both.

Clive was no aberration. An argument could be made that the greatest military mind America ever produced was Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, yet he was such a terrible student he was perpetually on the verge of expulsion from West Point. Another hopeless student, who fared even worse academically at West Point than Jackson, ought to ring a bell: Ulysses S. Grant. Meanwhile, the military’s academic superstar, the absolute darling of West Point, was George McClellan. All McClellan’s glowing report cards, however, did not save him from going down in history as one of the worst generals of all time.

Churchill himself may have been drawn to Clive’s biography for its shared chords with his own. Young Winston endured far more beatings from angry teachers than he won academic prizes. His literary genius did not seem to help him in school at all, he just didn’t have the temperament of the obedient student. His rise to fame came as a result of deliberately seeking out adventure, traveling all across the world to involve himself in as many faraway battles as he could find.

What would history look like if he, and all those other subpar students of the past, had been drugged to fit the mold of the good student, as so many of our subpar students are today?

I’m not attacking good students. Like I said, I was one, too. As Clive of India could tell you, we will always need good students, because we will always need good bureaucrats. But there is more – much more – to life than bureaucracy. Isn’t there?

Is there still adventure out there? Is there any room in 21st century America for a pioneer spirit? Are there territories left to discover, worlds – real or metaphorical – left to conquer? Can a young man still “go west,” or has the west already been won? Is there heroism in this life, or only in video game simulations?

If you think there’s nothing left in humanity’s future but “the atmosphere of the counting-house,” well, all I can say is I hope you’re wrong. History certainly suggests you are. Life doesn’t have to be boring. There is a whole world of adventure out there, there always has been, there always will be. Don’t give up on the world, and your child, just yet. The next time her teacher complains about her academic struggles and suggests you consider medicating her, it might be worth asking, “Have you ever heard of Robert Clive?”

Currently in the throws of raising a 13 year old young man, who is fond of arguing, your article inspires me to look beyond my current frustration and focus on the adventure!

Such a great article, thanks for writing and sharing it with us. I can't imagine what life would be like if I was a kid today.