David McCullough is not often this wrong. His mistake, however, is understandable – it is, after all, a defining error of our age.

Let’s back up. McCullough is the beloved historian whose books have brought the American story to life for millions of readers. I cannot recommend his work highly enough; you can’t go wrong with any of his books.

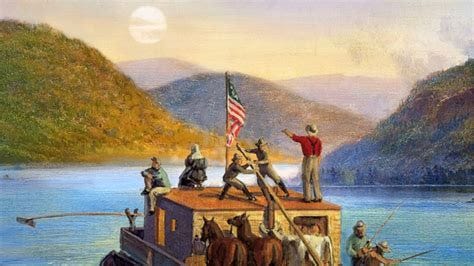

In this case, we are exploring the American West with The Pioneers. By West, I don’t mean California, or even Nebraska. No, in the early days following the War of Independence, the wild, untamed west was… Ohio! Imagine that. Imagine, too, packing up your children in a wagon, leaving behind your small New England town, and trying to survive a months-long trek through the uncharted wilderness, over mountain ranges, across raging rivers, to finally arrive… in more wilderness! To spend months upon arrival sleeping in a hollowed-out tree trunk while you cut down enough trees, and pull out enough tree roots, to make a clearing for a house … which you then have to build yourself. All the while knowing that this settlement, like so many nearby, might vanish overnight, whether in an outbreak of disease or an Indian attack. Not a life for the faint or heart (or back). Now imagine further that, while doing all the above, you also find time for a small side-hustle: building a civilization, with universities and museums and courthouses still going strong to this day. This is the awe-inspiring, heroic story of the settlers who built America.

The settlers’ most remarkable act, one that historians of a later generation would rank alongside the Magna Carta and the Declaration of Independence, was The Northwest Ordinance of 1787. As McCullough puts it, the Ordinance, which, among other articles, banned slavery in the new territory, “would prove to be one of the most far-reaching acts of Congress in the history of the country.”

For our purposes, I bring your attention to the Ordinance’s establishment of public education in the territory. In its own words:

religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.

Here is McCullough’s direct response. See if you can spot his error:

That such emphasis be put on education in the vast new territory before even one permanent settlement had been established was extraordinary.

Did you catch it? Read the Ordinance’s words and McCullough’s once more if you didn’t. If you missed it, don’t worry, you’re probably making the same error he did; it’s one of the most common errors around, and if you went and took a class at the local college on the American founding, I guarantee your professor would make it too.

Ok, here goes. Did the Ordinance put an emphasis on education, as McCullough writes? No! The emphasis is on religion, morality, and knowledge, and on how these are necessary to good government and happiness. Education is not the emphasis, education is the means of achieving the emphasized goal of spreading religion, morality, and knowledge.

Let’s take a shot at rephrasing the ordinance, dumbed down, and see where we come out. One version might sound like this:

An educated population is really important, which is why we need to encourage lots and lots of public education.

Another:

A religious, moral, and knowledgeable population is really important, which is why we need to encourage religion, morality, and knowledge.

The first attempt certainly emphasizes education; the second doesn’t even contain the word “education.” Yet the latter is far closer to the meaning of the Ordinance than the former.

Am I quibbling? Hardly. CS Lewis once stumbled upon a seemingly trivial phrase in a popular high school English textbook. The authors explained that our feelings are subjective, not tied to objective reality – we are not making a remark about the beauty of a waterfall, but about our own subjective feelings about the waterfall. Lewis got two masterpieces, The Abolition of Man and its fictional counterpart, That Hideous Strength, out of that mistaken lesson. We look back on those works as remarkable prophecies, but to Lewis, it was a simple matter of logic – begin at the wrong starting place, as the textbook in question did, and the overthrow of objective truth, culminating in the loss of one’s own divine soul, is a frank inevitability.

I’m arguing that a similar flaw befell America – by confusing the emphasis of a phrase, we ended up losing our national soul.

In the time of the settlers, as was the case throughout most of history, the divide between religion and education was a distinction without a difference. Education as an endeavor was profoundly religious in nature. As Professor Esolen reminds us only this week, “the university was a Medieval guild, born from the bosom of the Church.” The very word university illustrates this: “It would be a union bound by union: by a common faith in the God who made the universe, in whom we live and move and have our being.”

Ok, so that was Europe in the 12th century… what about America? Well, when Harvard adopted its motto, Veritas, in 1643, its Puritan founders were referring not to CDC fact checks, but to God’s Truth. Apparently that wasn’t clear enough for some, so by 1650 they changed the motto to In Christi Gloriam (“For the Glory of Christ”).

Did settlers in faraway Ohio a century and a revolution later share Harvard’s, er, “emphasis”? Per McCullough, the driving force behind the Northwest Ordinance’s stance on education – as well as its abolition of slavery – was Manasseh Cutler. To be precise, the Reverend Manasseh Cutler. Here is a typical thought of his, from a sermon he gave in the new territory he had so much to do with establishing:

Such is the present state of things in this country, that we have just ground to hope that religion and learning, the useful and ornamental branches of science, will meet with encouragement, and that they will be extended to the remotest parts of the American empire … Here may the Gospel be preached to the latest period of time; the arts and sciences be planted; the seeds of virtue, happiness, and glory be firmly rooted and grow up to full maturity.

If that passage were ever to be assigned in an Ohio public school today, it would come with a trigger warning. As for contemporary Harvard dedicating itself to the glory of Christ, or American universities in general rediscovering their medieval Christian mission, dream on. Quite the opposite.

The irreplaceable Joy Pullman recently explained that Christians are now effectively banned from teaching in our public schools. That story is from Minnesota, which once was governed by the Northwest Ordinance. In Cutler’s Ohio, well, this week we learned of teachers deceiving parents in order to teach CRT, subverting the Biblical truth that race does not matter.

With those and countless other examples of public education in the 21st century in mind, recall the pioneers’ words:

religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.

As long as education stays true to its past and cultivates faith and virtue, McCullough’s mistake doesn’t matter. But once education becomes unmoored from its origins, once it becomes openly hostile to religion, we betray our own origins – and condemn our future – by continuing to “emphasize” schooling. Our founders, pioneers like the Reverend Cutler, spread the gospel of public education not for its own sake but because such education in turn spread the Gospel. To achieve that good government and happiness they envisioned, our task today is not to encourage public education as it currently exists – it is to remake it in His image.

I wrote last week about the myth of neutrality when it comes to medical research. It is the same with education. Let us return to The Abolition of Man, and borrow one of Lewis’s images: an attack of education on religion is “a rebellion of the branches against the tree: if the rebels could succeed they would find that they had destroyed themselves.”

Dear reader, I know it won’t be easy. We will not reclaim public education for our children, very likely not for our children’s children. We have many trees to fell, many roots to dig up – and once we accomplish that, we will have many houses to build. It is not work for the faint of heart. Yet go back and read McCullough. There, in the wilds of Ohio, our forefathers laid the foundations for schools and universities, not for themselves, not for their children or their children’s children, but for “the latest period of time.” Hard as our struggle will be, we truly do have it so much easier – they didn’t even have air conditioning! Look to their example, be of good cheer and firm purpose, and embrace that pioneer spirit. With God’s grace, we can conquer the wilderness once more.

Thank you for linking to this article in today's substack. I don't think I followed you yet back in January, but this article is truly a joyful inspiration for the work at hand. I cannot count the trees that need be felled in Bay Area public schools - we are truly lost in a forest of atheist modernity; but we will continue on, accepting the call and the task with good cheer, as you propose.

If we're not founded on the rock then we will be washed away...